WHY DO REFUGEE CHILDREN CONTINUE TO TAKE PERILOUS JOURNEYS TO REACH THE UK?

Full article published 27 April, 2020 in Culture and Capitalism

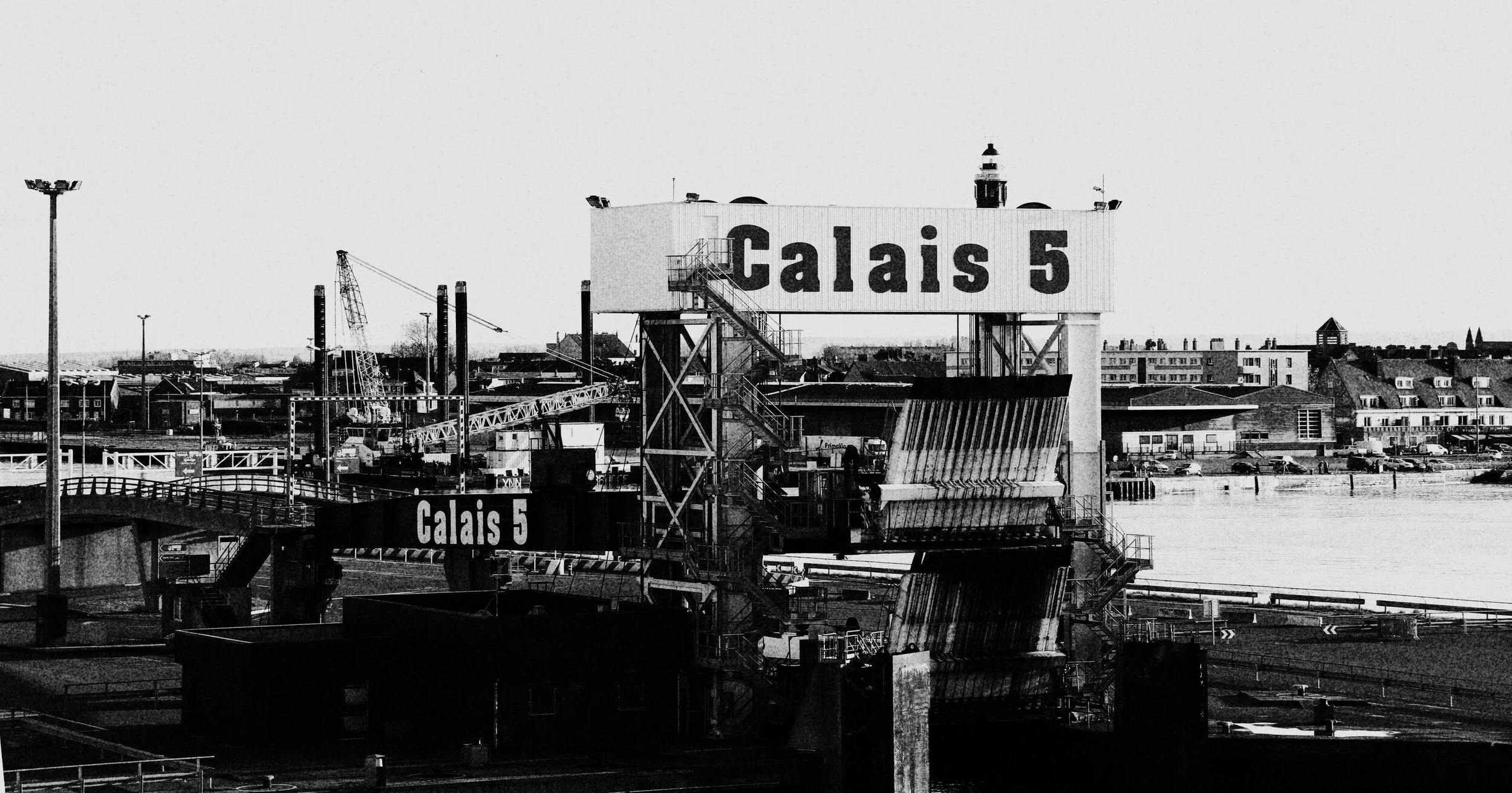

Port of Calais, 2020

In January, I revisited the refugee camps in Northern France, where I have volunteered since 2016. There, I met a medic who had treated a 13-year-old boy with fourth-degree burns all over the inside of his mouth: scars from pepper spray that police sprayed into his mouth in a recent camp demolition. Why was that child there, even after years of policies aimed at protecting children? I explain below why the Dubs Amendment—once hailed by conservatives and liberals alike as a life-saving measure—ultimately failed. Taking this as a lesson, I explore how future legislation might truly protect unaccompanied refugee children.

Section 67 of the UK’s Immigration Act 2016, widely known as the Dubs Amendment, requires the UK government to act “as soon as possible” to relocate and support unaccompanied refugee children in Europe. In doing so, it makes unaccompanied children an exception to the trend of externalised, aggressively-enforced borders that make applying for asylum in the UK incredibly dangerous, even for those who qualify. The EU’s Dublin III regulations specify that families have a legal right to remain together, which in the past gave individual refugees with family connections in the UK a pathway to protection. In contrast, the Dubs Scheme was the only measure providing unaccompanied minors who sought asylum in the UK with a safe, legal pathway to enter the country. For the 3,000 refugee children originally promised safe passage and protection under the Dubs amendment, only 220 had arrived as of September 2019. After Boris’ election victory, the government removed it from the Brexit bill.

Since 2016, the Dubs amendment demanded that the government support and relocate eligible unaccompanied refugee minors to the UK; however, in that time the situation only deteriorated. In 2020, children’s refugee centers in the UK are bursting at the seams: some have witnessed a 50% increase in demand for their services, according to the Guardian. The minors they serve sailed dinghies or jumped lorries to cross the Channel, taking great risks to reach the UK simply to place asylum claims.

While the Dubs Amendment addressed the issue of unaccompanied minors previously denied any legal pathways through which to apply for asylum, by focusing its passage on ideas of “deservingness”, it implicitly bowed to the general rule of ignoring international human rights law by authorities in Calais. Given the inhumane and chaotic conditions of refugee camps there, it could not function as it was intended to. The Conservative government’s removal of the amendment from the Brexit bill illustrates how purely symbolic the legislation grew to be: by removing Dubs, they reiterated their tough, no-nonsense stance on immigration.

Calais’ close vicinity to the UK attests to the challenges of enacting even relatively straightforward legislation within a context of inhumane, chaotic conditions. Lord Alf Dubs, who gave the amendment its name, arrived in the UK as a child refugee. He spearheaded the 2016 amendment, calling upon the legacy of Kindertransport as a humanitarian ideal. He recounted his experience of visiting the Jungle camp later that year, after the passage of Dubs: “The conditions are awful – children living in shacks, in tents very makeshift, with just one meal a day… with no support system”. His observations reflected the precarious situation in Calais, highlighting how difficult the implementation of the Dubs amendment was, considering the lack of facilities or professional support.

In order for the majority of asylum-seekers to petition for asylum in the UK, they must first arrive on British soil, creating a dangerous situation for lorry drivers, ferry operators and migrants alike. Calais lacks either a French or British asylum office, making it impossible for migrants to apply for asylum from there. Activist groups including Help Refugees and Care4Calais have urged the government to create “safe, legal routes” to asylum, but after more than two decades of migrants living in Calais, they still wait.

…

Full article available at Culture and Capitalism, University of Sussex Anthropology Blog

UK / France Border, Calais, France, 2016. Isabel Soloaga.